Eduardo Merizio Raad Camargo1; Ricardo Kozima Veríssimo1; Lívia Camargo Martinati1; Fernanda Sampaio Zottmann1; Samantha Lynn Oliveira Roberts1; Markos Kozima Veríssimo1; Adriana Haidar Spanghero1; André Maurício Sleiman Raad Camargo2; Taíse Tognon3

DOI: 10.17545/eOftalmo/2024.0023

ABSTRACT

This report describes a case of unilateral corneal ectasia after photorefractive keratectomy, with no preoperative evidence of ectatic disease. A 33-year-old male patient underwent bilateral photorefractive keratectomy. Preoperative corneal tomography (CT) showed normal parameters and a low ectasia-risk score, despite slight asymmetry on the anterior surface of the left cornea. Three years after the procedure, he developed ectasia in his left eye. CT revealed inferior steepening, increased posterior elevation, and corneal thinning, suggestive of ectasia. The patient was treated with corneal cross-linking, and his condition stabilized. This report highlights the importance of careful preoperative assessment and long-term follow-up, even in photorefractive keratectomy candidates whose preoperative examinations show no signs of corneal ectasia.

Keywords: Corneal ectasia; Photorefractive keratectomy; Refractive surgery; Corneal tomography; Cross-linking.

RESUMO

Relatar um caso de ectasia corneana unilateral após ceratectomia fotorrefrativa, sem evidência de ectasia corneana no pré-operatório. Paciente masculino, 33 anos, submetido à ceratectomia fotorrefrativa bilateral. A tomografia pré-operatória apresentava parâmetros normais e escore de risco para ectasia baixo, apesar de discreta assimetria na superfície anterior da córnea esquerda. Três anos após o procedimento, desenvolveu ectasia no olho esquerdo. A tomografia revelou encurvamento inferior, aumento da elevação posterior e afinamento corneano, compatíveis com ectasia. O paciente foi tratado com crosslinking corneano, com estabilização do quadro. Este relato destaca a importância de uma avaliação pré-operatória criteriosa e do seguimento a longo prazo, mesmo em candidatos à ceratectomia fotorrefrativa com exames pré-operatórios sem evidência de ectasia corneana.

Palavras-chave:

Relatar um caso de ectasia corneana unilateral após ceratectomia fotorrefrativa, sem evidência de ectasia corneana no pré-operatório. Paciente masculino, 33 anos, submetido à ceratectomia fotorrefrativa bilateral. A tomografia pré-operatória apresentav

INTRODUCTION

Corneal ectasia is an uncommon but serious complication of refractive surgery. This condition occurs more frequently after laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK)1-4, with an incidence 4.5 times higher in eyes without preoperative risk factors compared with photorefractive keratectomy (PRK)5. However, cases of post-PRK ectasia have been reported in the literature1,6-10, and although the risk factors have not yet been fully elucidated, preoperative corneal tomographic abnormalities and a thin cornea may contribute to its development2.

The literature on post-PRK corneal ectasia is limited, with only a few reports available. In this case report, we present a patient with a tomographic pattern of asymmetrical astigmatism that progressed to unilateral ectasia 3 years after PRK.

CASE REPORT

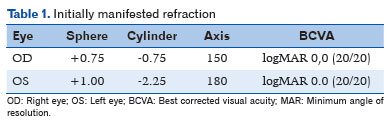

A 33-year-old male patient who had been followed since 2017 and had no family history of keratoconus or signs of the disease on slit-lamp biomicroscopy attended a routine appointment in January 2020, stating that he wished to undergo surgical correction of his refractive error. The refraction results are shown in Table 1.

In preoperative examinations, corneal tomography (CT, Pentacam) was performed, and a tomographic map of the cornea was obtained. In the right eye, the elevation values of the anterior and posterior surfaces were within the normal range. In the left eye, asymmetry was observed on the anterior surface, whereas the posterior surface remained within normal parameters.

Analysis of the sagittal map of the anterior corneal surface showed the presence of with-the-rule astigmatism in both eyes. The simulated keratometry values for the anterior corneal surface were 41.2/42.1 diopters (D) in the right eye and 40.9/43.00 D in the left eye.

The maximum corneal curvature (Kmax) was 42.3 D in the right eye, with a central corneal thickness (CCT) of 529 µm and a thinnest point (TP) of 527 µm. In the left eye, Kmax was 43.5 D, with a CCT of 528 µm and a TP of 523 µm (Figure 1).

Analysis using the Belin/Ambrosio Enhanced Ectasia Display (BAD) system showed values of 0.41 in the right eye and 1.17 in the left eye. No high-risk values were identified in either cornea. Additionally, the anterior and posterior corneal elevations were within the normal range in both eyes, with no evident abnormalities (Figure 2).

The patient underwent PRK with mitomycin application using the Alcon Wavelight EX500 laser in August 2020. The procedure was performed with an optical zone diameter of 6.5 mm in both eyes. The total ablation depth, including the epithelium, was 11.25 µm in the right eye and 30 µm in the left eye.

The surgery was uneventful intraoperatively, and the patient’s condition progressed satisfactorily during the postoperative period with no complications. The patient continued regular follow-up appointments over the years, with no significant changes. In June 2023, he presented for a routine examination with no visual complaints. Refraction remained stable, with visual acuity of 20/20 in both eyes and no evidence of visual decline.

However, during the skiascopy examination, a scissor reflex was observed, suggesting irregular astigmatism. Given this finding, additional tests were requested for further investigation.

CT showed signs of corneal ectasia in the left eye, including focal steepening in the inferior region of the cornea, evident on the axial curvature (anterior sagittal) map as a localized increase in corneal curvature. Kmax reached 45.6 D, contrasting with flatter areas in the superior region, thereby suggesting a characteristic asymmetrical pattern.

Moreover, there was an increase in the elevation of the posterior corneal surface, with values up to +28 μm on the posterior elevation map, which reinforced the diagnosis of ectasia. The corneal thickness map showed thinning in the central–inferior region, with a TP of 486 μm, consistent with the area of ectasia. None of these signs were found in the right eye (Figure 3).

The patient underwent corneal cross-linking (CXL) in the left eye in August 2023, with the aim of stabilizing the post-PRK corneal ectasia. The procedure was uneventful intraoperatively, and the postoperative course was satisfactory, with no complications. At the 6-month follow-up, the corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 20/20, with a refraction of 0.00−1.00 × 180º.

In March 2024, CT of the left eye was performed again to monitor the response to treatment. The scan showed tomographic stability, with no evidence of ectasia progression.

The anterior axial curvature map showed a Kmax of 46.2 D, similar to the previous examination, with no expansion of the steepening area. The corneal thickness map showed a TP of 471 μm, with preserved concentric distribution and no significant changes compared with the prior examination. On the posterior elevation map, there was no progression of corneal protrusion.

These findings are consistent with the efficacy of CXL, indicating biomechanical stabilization of the cornea and no progression of ectasia during the interval between examinations.

DISCUSSION

Corneal ectasia after refractive surgery is an infrequent but significant complication, characterized by progressive thinning and protrusion of the cornea, leading to irregular astigmatism and loss of corrected visual acuity. Although more commonly associated with LASIK, its occurrence after PRK has been reported in isolated cases, indicating that factors other than flap creation may contribute to biomechanical weakening of the cornea5,11. In this report, we describe a case of unilateral corneal ectasia in a 33-year-old patient that occurred 3 years after transepithelial PRK—a scenario that aligns with the rarity and complexity of a similar case of unilateral ectasia after bilateral PRK reported by AlShawabkeh et al.8. We underscore the need to better understand the predisposing factors and clinical implications of this condition, particularly in surface ablation procedures such as PRK, which theoretically preserve more structural integrity than LASIK2.

The clinical presentation in this case (unilateral ectasia in one eye with no obvious signs of preoperative keratoconus) is consistent with findings from other reports in the literature. AlShawabkeh et al.8 described a case of unilateral ectasia diagnosed 15 months after bilateral transepithelial PRK in a patient with a normal preoperative CT and no classic risk factors, such as reduced pachymetry or suspicious keratoconus indicators. Similarly, our patient had subtle tomographic asymmetry in the affected eye (BAD value of 1.17) but did not meet the diagnostic criteria for keratoconus before surgery. Another report by Alvani et al.1 documented bilateral ectasia 7 years after PRK, with confocal microscopy revealing subtle changes in keratocyte density that suggested a pre-existing structural impairment not detected using conventional methods. The unilaterality observed in our case and in that of AlShawabkeh et al.8 contrasts with the bilaterality reported by Alvani et al.1, indicating that local factors or individual biomechanical asymmetries may influence the manifestation of ectasia.

The etiology of post-PRK ectasia is multifactorial, involving an interaction between preoperative factors, surgical characteristics, and the intrinsic biomechanical properties of the cornea. The Ectasia Risk Score System, validated for LASIK by Randleman et al.12, identifies abnormal tomography, low residual stromal thickness, and thin pachymetry as the main predictors3,13-15. Although these criteria are less applicable to PRK because no flap is created, studies indicate that subtle tomographic asymmetries and thinner corneas may also increase the risk in surface ablation procedures2. In our case, the preoperative central pachymetry was adequate (528 µm in the left eye), and the 30-micron ablation depth was within safe limits7. However, the pre-existing tomographic asymmetry, although below the threshold for suspicion, may have indicated a latent biomechanical vulnerability.

In addition to pachymetry and ablation depth, another factor considered in the preoperative assessment was the percentage tissue altered (PTA), a calculation used to estimate the risk of ectasia (especially in LASIK), where a PTA of <40% is generally considered safe2,4,6. PTA was calculated for our patient, and based on these values, LASIK surgery was initially considered because the results were well below this threshold. The calculations were as follows:

• PTA (right eye): (120 + 11.25) / 527 = 0.24

• PTA (left eye): (120 + 30) / 523 = 0.28

These results, both below 40%, indicated that the LASIK technique was a viable option for this patient. However, due to the presence of corneal asymmetry in the left eye, we opted for the PRK technique, which carries a lower risk of corneal ectasia compared with LASIK in borderline cases such as the present case5. This decision reflects a cautious approach, consistent with recommendations in the literature suggesting greater vigilance in patients with suspicious CT findings, even when other parameters, such as PTA, indicate low risk8. Despite this more conservative choice, the development of ectasia in the left eye suggests that PRK, although less invasive, does not completely eliminate the risk in corneas with underlying biomechanical fragility.

The literature indicates that some cases of post-PRK ectasia, even in the absence of identifiable risk factors, may represent the progression of previously undiagnosed subclinical keratoconus. A systematic review reported an incidence of up to 20 cases per 100,000 eyes undergoing PRK without apparent risk factors, reinforcing this hypothesis5. Confocal microscopy, which was used by Alvani et al.1, could have detected early structural changes but was not performed in our patient. Moreover, ablation depth and PTA, although within acceptable limits, may not fully capture the risk in patients with individual predispositions, such as biomechanical or metabolic alterations not detected using conventional tests8.

This case highlights the importance of a comprehensive preoperative assessment and prolonged monitoring after PRK, even in patients with no obvious risk factors. The presence of tomographic asymmetries, however subtle, should be considered a warning sign, as emphasized by Sorkin et al.2. Advanced tools, such as corneal biomechanical analysis (e.g., Corvis ST) and combined tomographic indices (e.g., BAD), have been identified as promising alternatives to improve risk screening, especially in borderline cases8. Moreover, corneal epithelial analysis (epithelial thickness mapping through high-resolution optical coherence tomography) increases the accuracy of preoperative screening; compensatory epithelial changes can mask early stromal irregularities and help elucidate astigmatism that is “unexplained” by tomography. Routine incorporation of this test in borderline cases could reduce false negatives in screening for subclinical ectasia16. However, although Corvis ST is a promising tool, its data are not yet fully understood, and more studies are needed before it can be included in validated clinical protocols5,17. Furthermore, the occurrence of ectasia after a surface procedure challenges the perception that PRK is intrinsically safer than LASIK, suggesting that surgeons should adopt a cautious approach regardless of the technique5.

Treatment with CXL was successful in our patient, stabilizing the progression of ectasia, an outcome consistent with previous reports6,8. This reinforces the role of CXL as an effective intervention in cases of post-refractive ectasia but underscores the importance of prevention. Strategies such as the use of artificial intelligence for risk prediction, as suggested by AlShawabkeh et al.8, may represent the future of preoperative screening and help reduce the incidence of this complication.

Finally, in suspicious cases or when any abnormality is present on the initial CT that cannot be clinically explained, it is recommended to confirm the patient’s refractive stability (i.e., no significant changes for at least 12 months) and repeat the CT scan at a subsequent visit before indicating surgery. This prudent approach supports the detection of subclinical progression and increases safety in candidate selection.

This report has limitations typical of a single case study, including the absence of preoperative biomechanical data and the lack of confocal microscopy results to assess cellular changes. A 3-year follow-up, although significant, may not be sufficient to exclude the risk of late ectasia in the contralateral eye, as observed in cases of asymmetric progression7. Moreover, the exact contribution of factors such as ablation depth or biomechanical properties remains speculative without more detailed analysis.

Future studies should prioritize the development of specific risk criteria for PRK as well as the integration of advanced imaging technologies and genetic biomarkers to identify vulnerable patients8. Longitudinal studies comparing LASIK and PRK could clarify differences in the incidence and mechanisms of ectasia, while trials evaluating the impact of prophylactic CXL in high-risk cases could offer new preventive strategies5.

REFERENCES

1. Alvani A, Hashemi H, Pakravan M, Aghamirsalim MR. Corneal ectasia following photorefractive keratectomy: a confocal microscopic case report and literature review. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2023;86:e20210296.

2. Sorkin N, Kaiserman I, Domniz Y, Sela T, Munzer G, Varssano D. Risk assessment for corneal ectasia following photorefractive keratectomy. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:2434830.

3. Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, Stulting RD. Risk assessment for ectasia after corneal refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):37-50.

4. Santhiago MR, Giacomin NT, Smadja D, Bechara SJ. Ectasia risk factors in refractive surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016 Apr 20;10: 713-720.

5. Moshirfar M, Tukan AN, Bundogji N, Liu HY, McCabe SE, Ronquillo YC, Hoopes PC. Ectasia after corneal refractive surgery: a systematic review. Ophthalmol Ther. 2021;10(4):753-76. doi:10.1007/s40123-021-00383-w.

6. Diniz D, Andrade FMX, Chamon W, Allemann N. Corneal suture for acute corneal hydrops secondary to post-LASIK ectasia: a case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2020;83(6):538-42.

7. Roszkowska AM, Sommario MS, Urso M, Aragona P. Post photorefractive keratectomy corneal ectasia. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(2):315-7.

8. AlShawabkeh M, Al Sakka Amini R, Alni’mat A, Al Bdour MD. Unilateral corneal ectasia after bilateral transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy. Cureus. 2024;16(12):e76189.

9. Malecaze F, Coullet J, Calvas P, Fournié P, Arné JL, Brodaty C. Corneal ectasia after photorefractive keratectomy for low myopia. Ophthalmology. 2006 May;113(5):742-6.

10. Chiou AGY, Bovet J, de Courten C. Management of corneal ectasia and cataract following photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006 Apr;32(4):679-80.

11. Xia LK, Yu J, Chai GR, Wang D, Li Y. Comparison of the femtosecond laser and mechanical microkeratome for flap cutting in LASIK. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015 Aug 18;8(4):784-90.

12. Randleman JB, Trattler WB, Stulting RD. Validation of the Ectasia Risk Score System for Preoperative Laser in Situ Keratomileusis Screening. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 May;145(5):813-8.

13. Tabbara KF, Kotb AA. Risk factors for corneal ectasia after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(10):1618-22.

14. Randleman JB, Russell B, Ward MA, Thompson KP, Stulting RD. Risk factors and prognosis for corneal ectasia after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2003 Feb;110(2):267-75.

15. Klein SR, Epstein RJ, Randleman JB, Stulting RD. Corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis in patients without apparent preoperative risk factors. Cornea. 2006;25(4):388-403.

16. Abdelfadeel SM, Khalil NM, Khazbak LM, Sidky MK. Role of epithelial mapping in the differentiation between early keratoconus and high regular astigmatism using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J Egypt Ophthalmol Soc. 2023;116(1):7-14.

17. Zhang M, Zhang F, Li Y, Song Y, Wang Z. Early diagnosis of keratoconus in Chinese myopic eyes by combining Corvis ST with Pentacam. Curr Eye Res. 2020;45(2):118-123.

| AUTHORS INFORMATIONS |

|

|

» Eduardo Merizio Raad Camargo https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8910-6900 http://lattes.cnpq.br/2447541377421780 |

|

» Ricardo Kozima Veríssimo https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8607-2927 http://lattes.cnpq.br/6140706254072037 |

|

» Lívia Camargo Martinati https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3276-2356 http://lattes.cnpq.br/4975444940867171 |

|

» Fernanda Sampaio Zottmann https://orcid.org/0009-0000-2432-3419 http://lattes.cnpq.br/7054536895384159 |

|

» Samantha Lynn Oliveira Roberts https://orcid.org/0009-0003-6137-2529 https://lattes.cnpq.br/1148947466721901 |

|

» Markos Kozima Verissimo https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2336-9884 http://lattes.cnpq.br/2142317939979093 |

|

» Adriana Haidar Spanghero https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0317-9130 http://lattes.cnpq.br/3051224074524438 |

|

» André Maurício Sleiman Raad Camargo https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3285-4387 http://lattes.cnpq.br/6548444966583394 |

|

» Taíse Tognon https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9605-7647 http://lattes.cnpq.br/0431359304865058 |

Funding: The authors declare no funding.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Received on:

July 14, 2025.

Accepted on:

October 31, 2025.